2014-06-14 11:44:00

Kurdistan's Peshmerga forces secure an area in Kirkuk city, northern Iraq, 12 June 2014. Kurdish forces of Iraq's autonomous Kurdistan Region have taken complete control over the disputed city of Kirkuk after the Iraqi army withdrew from there, a Kurdish military spokesman was cited as saying. (Khalil Al-A'nei/EPA)

BY BEN VAN HEUVELEN

ANKARA, Turkey — As security forces in northern Iraq crumble under the onslaught of Islamist militants, the autonomous Kurdistan region — a bastion of stability — is rapidly laying the groundwork to become an independent state.Iraqi forces have continued to cede territory to an insurgency led by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which is swiftly advancing toward Baghdad after capturing Mosul on Tuesday. Kurdistan’s military forces, known as the pesh merga (or “those who face death”), have taken over many of the northernmost positions abandoned by the national army, significantly expanding the zone of Kurdish control.

“As the Iraqi Army has abandoned its posts . . . Peshmerga reinforcements have been dispatched to fill their places,” Jabbar Yawar, secretary general of the Ministry of Pesh Merga Affairs, said in a statement.

The Kurds have also recently taken a big step toward economic independence by deepening a strategic alliance with the Turkish government. In late May, they began exporting oil via a pipeline through Turkey, with the revenue set to flow into a Kurdish-controlled bank account rather than the Iraqi treasury.

“This economic independence is vital for the Kurdistan region,” Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani said in an address to the Kurdish parliament last month. “We will not stop here.”

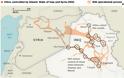

Ethno-religious map of Iraq

Strained relations

Since the beginning of the year, Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has responded to Kurdish oil ambitions by cutting the monthly distribution of the region’s share of the national budget. The Iraqi government has also filed an international arbitration claim against Turkey for facilitating the exports, which Baghdad characterizes as smuggling, and has threatened to sue anyone who buys the oil.

With relations badly strained, there is little appetite in the Kurdish capital of Irbil to provide any military support to Maliki.

“The Iraqi government has been holding the Kurds hostage, and it’s not reasonable for them to expect the Kurds to give them any help in this situation without compromising to Kurdish demands,” said an adviser to the Kurdish government, speaking on the condition of anonymity to be candid.

The pesh merga say they have not tried to displace ISIS from territory it now controls.

“In most places, we aren’t bothering them [ISIS], and they aren’t bothering us — or the civilians,” said Lt. Gen. Shaukur Zibari, a pesh merga commander.

In his statement, Yawar said, “There is no need for Peshmerga forces to move into these areas.”

The United States has tried for several years to broker agreements to bring Irbil and Baghdad closer together, but the efforts have failed because the two sides have fundamentally different visions for the country. WhereasMaliki has pushed for centralized control — especially over the oil resources that provide 95 percent of state revenue — the Kurds have insisted that the constitution grants them almost total autonomy.

The conflict has been so tense recently that Kurdish leaders have obliquely suggested that, absent concessions from Maliki, they will hold a referendum on whether to declare independence — a measure that would almost certainly pass amid an upswell of Kurdish nationalism.

“The policy of the Kurdistan Regional Government is to never take a step backward,” Barzani said in his address to parliament. “If we do not arrive at any resolutions [with Baghdad], then we have other alternatives, and we will take them.”

Tensions have also been aggravated through the years by territorial disputes. In the aftermath of Saddam Hussein’s regime, which waged campaigns of ethnic cleansing, ethnic groups have made competing claims to a belt of land stretching across the country as the formal boundary between the Kurdistan region and federal Iraq remains unresolved.

The symbolic heart of these disputes has been the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, which some have called the Jerusalem of the Kurds. On Thursday, after the national army left, Kurdish flags were flying where Iraqi flags once were, and Yawar said Kurdish forces “now control Kirkuk city and the surrounding areas.” Even Iraqi government oil facilities were now being guarded by Kurdish forces, Kurdish security officials said.

Turkish lifeline

As the Kurds try to shore up their territory, they also need an economic lifeline, and they have turned to Turkey. Last year, the landlocked Kurds built an oil pipeline to the Turkish border and signed agreements to govern the export of oil and gas to the Mediterranean; now, crude has begun to flow.

Those exports, which began May 22, were a milestone. Although the Kurds have been able to export oil for years by truck, only a pipeline can enable them to sell enough oil to replace the revenue being withheld by Baghdad.

In the meantime, the Kurdish government is staying solvent through loans from companies and foreign banks, according to Barzani. Two officials involved in the Turkey deal, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the topic, said the Turkish government had granted a loan directly to the Kurds, but they did not disclose the amount or the terms.

Turkey’s willingness to facilitate such autonomy marks a dramatic reversal by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose administration once worried that an independent Iraqi Kurdistan might inspire Turkey’s own Kurdish minority to seek a similar outcome. Erdogan was swayed, ultimately, by a convergence of interests, particularly Turkey’s growing energy demands. Now, with the rise of ISIS, Iraqi Kurdistan also represents a geographic buffer between Turkey and the chaotic violence to the south.

“Turkey will use its influence in Irbil to discourage independence,” said one of the Turkish officials involved in the energy deal. “But if Kurdistan should become independent, then, to put it in financial terms, Turkey has bought that option.”

The question now facing the Kurds is whether they can hold the line against ISIS. The group has begun attacking some of the pesh merga’s forward positions and nearly killed the leader of the force, Sheik Jaafar Mustafa, with an IED targeting his convoy near Kirkuk, according to a pesh merga soldier stationed there.

So far, the pesh merga have been able to repel ISIS attacks, and the Kurdistan region seems to have the military capability — and the backing of a powerful neighbor — to succeed without the federal government.

Drawn to this relative stability, tens of thousands from besieged Mosul have sought refuge in the region. Among them were three top Iraqi generals; on Thursday, the Kurdish government put them on a plane to Baghdad.

Loveday Morris in Irbil contributed to this report.

Washington Post

InfoGnomon

BY BEN VAN HEUVELEN

ANKARA, Turkey — As security forces in northern Iraq crumble under the onslaught of Islamist militants, the autonomous Kurdistan region — a bastion of stability — is rapidly laying the groundwork to become an independent state.Iraqi forces have continued to cede territory to an insurgency led by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which is swiftly advancing toward Baghdad after capturing Mosul on Tuesday. Kurdistan’s military forces, known as the pesh merga (or “those who face death”), have taken over many of the northernmost positions abandoned by the national army, significantly expanding the zone of Kurdish control.

“As the Iraqi Army has abandoned its posts . . . Peshmerga reinforcements have been dispatched to fill their places,” Jabbar Yawar, secretary general of the Ministry of Pesh Merga Affairs, said in a statement.

The Kurds have also recently taken a big step toward economic independence by deepening a strategic alliance with the Turkish government. In late May, they began exporting oil via a pipeline through Turkey, with the revenue set to flow into a Kurdish-controlled bank account rather than the Iraqi treasury.

“This economic independence is vital for the Kurdistan region,” Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani said in an address to the Kurdish parliament last month. “We will not stop here.”

Ethno-religious map of Iraq

Strained relations

Since the beginning of the year, Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki has responded to Kurdish oil ambitions by cutting the monthly distribution of the region’s share of the national budget. The Iraqi government has also filed an international arbitration claim against Turkey for facilitating the exports, which Baghdad characterizes as smuggling, and has threatened to sue anyone who buys the oil.

With relations badly strained, there is little appetite in the Kurdish capital of Irbil to provide any military support to Maliki.

“The Iraqi government has been holding the Kurds hostage, and it’s not reasonable for them to expect the Kurds to give them any help in this situation without compromising to Kurdish demands,” said an adviser to the Kurdish government, speaking on the condition of anonymity to be candid.

The pesh merga say they have not tried to displace ISIS from territory it now controls.

“In most places, we aren’t bothering them [ISIS], and they aren’t bothering us — or the civilians,” said Lt. Gen. Shaukur Zibari, a pesh merga commander.

In his statement, Yawar said, “There is no need for Peshmerga forces to move into these areas.”

The United States has tried for several years to broker agreements to bring Irbil and Baghdad closer together, but the efforts have failed because the two sides have fundamentally different visions for the country. WhereasMaliki has pushed for centralized control — especially over the oil resources that provide 95 percent of state revenue — the Kurds have insisted that the constitution grants them almost total autonomy.

The conflict has been so tense recently that Kurdish leaders have obliquely suggested that, absent concessions from Maliki, they will hold a referendum on whether to declare independence — a measure that would almost certainly pass amid an upswell of Kurdish nationalism.

“The policy of the Kurdistan Regional Government is to never take a step backward,” Barzani said in his address to parliament. “If we do not arrive at any resolutions [with Baghdad], then we have other alternatives, and we will take them.”

Tensions have also been aggravated through the years by territorial disputes. In the aftermath of Saddam Hussein’s regime, which waged campaigns of ethnic cleansing, ethnic groups have made competing claims to a belt of land stretching across the country as the formal boundary between the Kurdistan region and federal Iraq remains unresolved.

The symbolic heart of these disputes has been the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, which some have called the Jerusalem of the Kurds. On Thursday, after the national army left, Kurdish flags were flying where Iraqi flags once were, and Yawar said Kurdish forces “now control Kirkuk city and the surrounding areas.” Even Iraqi government oil facilities were now being guarded by Kurdish forces, Kurdish security officials said.

Turkish lifeline

As the Kurds try to shore up their territory, they also need an economic lifeline, and they have turned to Turkey. Last year, the landlocked Kurds built an oil pipeline to the Turkish border and signed agreements to govern the export of oil and gas to the Mediterranean; now, crude has begun to flow.

Those exports, which began May 22, were a milestone. Although the Kurds have been able to export oil for years by truck, only a pipeline can enable them to sell enough oil to replace the revenue being withheld by Baghdad.

In the meantime, the Kurdish government is staying solvent through loans from companies and foreign banks, according to Barzani. Two officials involved in the Turkey deal, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the topic, said the Turkish government had granted a loan directly to the Kurds, but they did not disclose the amount or the terms.

Turkey’s willingness to facilitate such autonomy marks a dramatic reversal by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose administration once worried that an independent Iraqi Kurdistan might inspire Turkey’s own Kurdish minority to seek a similar outcome. Erdogan was swayed, ultimately, by a convergence of interests, particularly Turkey’s growing energy demands. Now, with the rise of ISIS, Iraqi Kurdistan also represents a geographic buffer between Turkey and the chaotic violence to the south.

“Turkey will use its influence in Irbil to discourage independence,” said one of the Turkish officials involved in the energy deal. “But if Kurdistan should become independent, then, to put it in financial terms, Turkey has bought that option.”

The question now facing the Kurds is whether they can hold the line against ISIS. The group has begun attacking some of the pesh merga’s forward positions and nearly killed the leader of the force, Sheik Jaafar Mustafa, with an IED targeting his convoy near Kirkuk, according to a pesh merga soldier stationed there.

So far, the pesh merga have been able to repel ISIS attacks, and the Kurdistan region seems to have the military capability — and the backing of a powerful neighbor — to succeed without the federal government.

Drawn to this relative stability, tens of thousands from besieged Mosul have sought refuge in the region. Among them were three top Iraqi generals; on Thursday, the Kurdish government put them on a plane to Baghdad.

Loveday Morris in Irbil contributed to this report.

Washington Post

InfoGnomon

ΦΩΤΟΓΡΑΦΙΕΣ

ΜΟΙΡΑΣΤΕΙΤΕ

ΔΕΙΤΕ ΑΚΟΜΑ

ΠΡΟΗΓΟΥΜΕΝΟ ΑΡΘΡΟ

Πορτογαλία: Απέρριψε την τελευταία δόση της τρόικα [video]

ΣΧΟΛΙΑΣΤΕ

![Πορτογαλία: Απέρριψε την τελευταία δόση της τρόικα [video]](https://images.newsnowgreece.com/68/684153/portogalia-aperripse-tin-teleftaia-dosi-tis-troika-video-1-124x78.jpg)